PART TWO

TO THE NEW COLONY.

“Weep sore for him that goeth away;

for he shall return no more, nor see his native land.”

Jeremiah 22 10

The Ship “INDIAN”, 522 tons, with two decks and sheathed in copper, had been built in Whitby only a year earlier. She had lately been especially fitted out to transport convicts. She had a crew of 45 and carried 12 cannon. She was the only ship to leave England (or Ireland) in 1810 with male prisoners. (The only other ship – “Canada” – carried 122 women.) She took 151 days to reach Port Jackson. The Master was Captain Barclay and Surgeon’s name was Maine. The owners were Munnery and others.

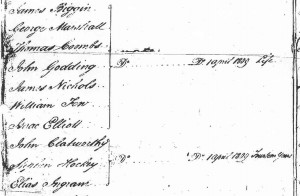

The Transportation Register for the period confirms that “George Marshall, tried at Somerset Assizes, 1 April 1809, sentenced to transportation for life was transported on the “INDIAN” leaving England July 1810[1] “ The Ship’s Indent [2] provided confirmation in the same terms.

The Indent listed all 200 transportees, including the group convicted at Taunton Castle on the same day.

In addition to the crew and convicts, a subaltern and thirty soldiers of the 73rd Regiment were on board. The men of 73rd Regiment, which was sent to replace the New South Wales Corps, (the ill fated ‘Rum Corps’) carried out various security duties on several convict transports in their progressive transfer to New South Wales. Originally Governor Macquarie was to command the Regiment in the Colony but was appointed Governor instead, prior to departure from England. He arrived in Port Jackson the previous year along with the first element of the Regiment to sort out the mess left by the rebellion against Bligh and its aftermath.

The cargo imported into the Colony consisted of “Rum, 4 casks equal to 318 gallons; brandy 2 casks, equal to 80 gallons; gin, 7 casks, equal to 288 gallons, all brought in by the Officers of 73rd Regiment. The ‘Indian’ also carried general cargo consisting of

“30 Hogsheads and Casks of Porter, 4 Cases of Noyua, 12 Barrels of Tar, 3 Casks of Paint, 100 Jugs of Turpentine and Paint Oil, 4 Cases of Hats, 12 Cases of Pickles, 5 Cases of Stationary and Saddlery, 2 Boxes of Pins and Umbrellas, 3 Cases of Perfumery, 8c., 2 Bales of Cloth, 3 Rolls of Painted Floor Cloth, 19 Casks of Dutch Cheese and Nails, 10 Packages of Shoes and Hardware, 3 Chests of Hyson Tea, 12 Casks of Coffee, 3 Casks of Sugar, and 80 Rolls of Tobacco[3]”

Following the very high death rate on earlier convict transports, the Government required a surgeon on board. Detailed instructions were issued to Masters and Surgeons in 1801. The need for proper ventilation and cleanliness was emphasised, and the Surgeon was given wide ranging responsibilities for health, medicines, diet as well as the need for the convicts to have fresh air and exercise. The death rate in the ten year period surrounding the “INDIAN’S” 1810 journey was an improvement over the early years of transportation. The instructions at the time however, were silent on the respective sphere of responsibilities of the Captain and the Surgeon respectively. So the on board authority of the Surgeon was unclear at the time of the “INDIAN” journey.. Nevertheless no less than ten of the “INDIAN’S” passengers died en route.[4] One of these died by drowning at Rio de Janeiro.[5] Governor Macquarie’s Despatch stated the nine “died of disease”. The Surgeon’s report is no longer to be found.

James Hardy Vaux, transported for the second time, and travelling under the name of James Lowe, wrote of the voyage in the following terms:

“ We…sailed in company with the “LION”, and the “CHICHESTER” store ship.[6] The former had on board the Persian Ambassador and suite, and was bound for Bombay. The latter was destined for St Helena, and we were to accompany them, under convoy, as far as the latitude of the Cape of Good Hope. Nothing but the usual routine of occurrences befell us on our voyage. We touched first at Madiera, and afterwards at Rio de Janeiro, but our stay at both places was short. The day after we quitted the latter in company with our Commodore and our store ship; both these vessels so far outsailed us, that we lost sight of them and separated, continuing our course alone and without interruption, and, with tolerable expedition, to the end of our voyage. On the 16 December, we anchored in Sydney Cove.”[7]

The prisoners were landed on 24 December, 1810 and taken to the jailyard for the Governor’s inspection. This muster was consistent with Macquarie’s regular practice. He sought to learn how prisoners had been treated on the voyage, to establish that they were in good health, and whether they had any complaints against the Master or the Surgeon. In this case, he was satisfied in each respect. The assembly gave him an opportunity to ascertain which convicts had trades or professions so that he could allocate them appropriately, especially to the settlers who at the time were short of labour in their agricultural pursuits. On this occasion, he was obviously well satisfied, for he reported in his later despatch that “the male convicts arrived in (the “INDIAN”) proved a very seasonable and acceptable supply for the Colony.” [8]

It is a reminder of the infrequency of ships’ arrivals at the time that after the ‘Indian’ arrived, Macquarie noted in his diary that he had “ a great number of Public and Private letters with good accounts of all our friends…”

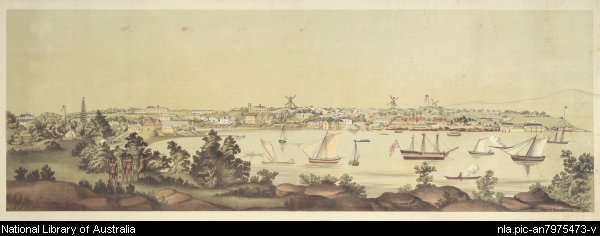

Sydney at the time consisted of 6,158 persons, with a further 2,389 on the Hawkesbury, 1,807 at Parramatta and 100 in Newcastle. Over 5000 were men, including 1,000 soldiers. The remaining 5,000 was evenly split between women and children. About 25 to 30% of the total were convicts. Settlement was about to spread to the south west districts of Airds, Appin and Bringelly. All the best soils in the Windsor-Richmond area were being farmed, and a series of floods had stressed the undesirability of dependence on the Hawkesbury district.[9]

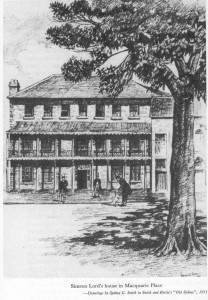

Fifty of the new arrivals then sent to the Hawkesbury for assignment to settlers. George Marshall was not among them. There is no certainty regarding his movements over the next few years. The 1811[10] and 1814[11] Musters record his presence in NSW, the latter specifically noting his assignment to “Mr Lord” and “Off stores” meaning Lord was funding all his costs. But there has been an assumption by his descendants, yet to be authenticated, that, perhaps having a background in textiles, he was assigned immediately to Simeon Lord. Whether this occurred immediately on arrival is not clear. Nevertheless, his background is consistent with the trades sought by Lord. At the time, Lord’s woollen mill, set up in the Bridge Street warehouse and very cramped, was busy enough to enable Lord to advertise that he had for sale coarse cloth, blankets, flannels and hats.[12]

In direct contrast to many modern day entrepreneurs, Lord started his career in Australia as a convict in 1791 having been convicted in Manchester of stealing a couple of hundred yards of calico muslin and other cloth. He started in business selling spirits and other merchandise for officers of the New South Wales Corp and by 1798 had purchased, a warehouse and dwelling in the centre of Sydney. He worked to bypass the officers’ control over imports and became very successful, buying directly from ships’ captains and acting as banker and agent for them He became well known as an auctioneer and landowner as well as being involved in anything else which might have earned him money. He built a fine house, Tank stream House, in Bridge Street beside the 1804 bridge. By 1809 his house was mansion, inn, store and dwelling house.[13] He supported the move to arrest Bligh in 1808 but did not get on with MacArthur, with whom he competed in business. As a successful emancipist he was well regarded by Macquarie who made him a magistrate in early 1810 and regularly invited him to dinner at Government House.[14]

Simeon Lord’s House, backing onto the Tank Stream. The wool manufactory where George Marshall and the other assignees worked was behind the house.

At the time, it was written of Lord in the following terms:

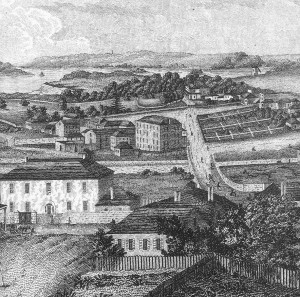

The rear of Simeon Lord’s House, looking from The Rocks, just across the Tank Stream, on what is now Bridge Street, leading up to the old Government House. The work buildings can be seen in the rear.

“The manufactures carried on in the Colony are confined to hats, coarse cloths, blankets, and woollen stockings. For these, the Colony is much indebted to the activity and enterprise of Mr S. Lord, who has established a manufactory at Botany Bay, about six miles from Sydney, where he employs a certain number of convicts, and from fifteen to twenty colonial boys. ….employing convict weavers, so many of whom have been transported to the Colony within the last five years.”[15]

Lord who had originally been sentenced for stealing textiles, ironically ended his career manufacturing his own…And so, later in this story, might George Marshall do the same.

By 1810, Lord had made his fortune as a trader, domestically and in the Pacific. But now he was being seriously disadvantaged by a financial downturn in both UK and the Colony. Over the period following Marshall’s arrival, he was setting up a textile manufacturing enterprise, starting with hats, which he commenced making in 1811. In 1815 he established a mill at Botany Bay to manufacture coarse cloths, blankets and flannels. He advertised for wool. From 1806 he employed over 20 years an average of twenty convicts on various types of manufacturing enterprise, he told Governor Darling in the twenties. Besides a creek in the swamps of Botany was his big woollen mill for producing woollen cloth, driven by a water wheel and with the cottages of sixty workers scattered round about.[16]

As noted above, we know that in 1814 Marshall had settled down as an assignee to Lord in Sydney, and probably had been so these past four years. He worked in the warehouse and factory on Lord’s Macquarie Place property, and he may have been worked for Lord out at Botany . His later request to the Governor for land he had ‘…discovered at Botany….” suggests he spent at least some time at Lord’s Botany factory.

Go to Part Three, click here.

- UK Public Records Office HO 11/2 Transportation Register 1810 to 1817↵

- SRNSW COD139 Page 351.↵

- HR of NSW Vol VII 1811 Page 609↵

- The Convict Ships 1787-1868. Charles Bateson.↵

- Sydney Gazette 22 Dec. 1810 and HR of NSW Vol VII P.609 Despatch by Gov. Macquarie 18 October 1811.↵

- The ‘Lion’ of 64 guns was commanded by Captain Henry Heathcote. She took part in the subjugation of Java in 1811. The ‘Chichester’ storeship, Master Wm Kirby, was wrecked in Madras Road on 2 May 1811 along with the ‘Dover’.↵

- The Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux. Written by Himself. 1819.↵

- HR of NSW 1811 Vol VII P.610.↵

- House of Commons Papers for 1812, Vol ii, Paper No 341.↵

- SRNSW COD 486↵

- Muster Roll 1814 P 197↵

- Nelson Cay. “Likely Lad.”↵

- Maureen Fry. “Sydney From The Rocks.”↵

- A History of James Ruse the Convict by Bill Jocelyn. Appendix A.↵

- Bigge Report 1822↵

- Sydney’s Highways of History. Geoffrey Scott.↵